Some of the world’s most renowned investors have made their fortunes by betting long – buying a stock, commodity or currency expecting the value to go up. Warren Buffett is probably the most recognised investor who adopted this approach. Meanwhile other investors have made their name by going short – which involves selling a borrowed asset with the intention of buying it back at a lower price. George Soros falls into this camp, with his bet against the British pound in the 1990s making him over $1 billion in one month and earning him the nickname ‘the man who broke the Bank of England’.1

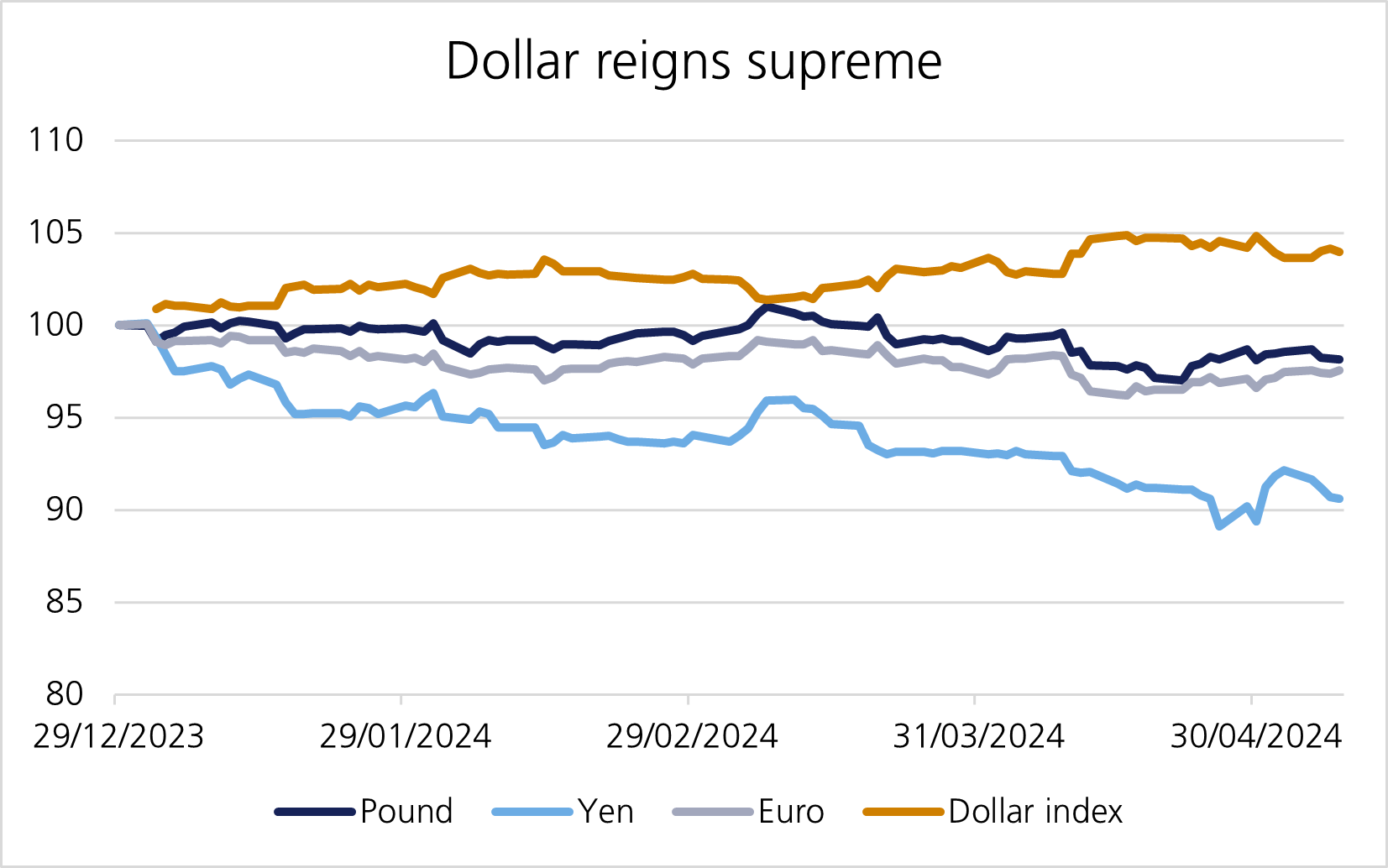

The logic behind Soros’ bet was that the pound and several other European currencies were priced too richly against the German deutsche mark, and that central banks and politicians would be unable to maintain artificially high exchange rates. This was only possible due to the exchange rate mechanism, a framework where countries manage the values of their currencies within a range, ideally creating stability in exchange rates. Following Soros’ and other hedge funds’ bets against the pound in 1992, the UK withdrew from the system. The pound is now part of a floating exchange rate system, where the value of sterling is determined by market supply and demand. With the timing of rate cuts in the US pushed back to later this year, this has seen the dollar strengthen further compared to the broad basket of currencies. This limits other central banks’ ability to cut rates, as currency weakness will likely lead to higher price pressures.

Yesterday, the Bank of England (BoE) indicated it is more comfortable with cutting rates. Governor Andrew Bailey said at the press conference Thursday it is “likely we will need to cut the bank rate” and make monetary policy “less restrictive in coming quarters.”

It is worth taking a closer look at how the members voted. Deputy Governor for Markets and Banking Dave Ramsden voted for hikes in 2021 and 2022, with other members following his lead soon after. Yesterday, Ramsden joined Swati Dhingra in voting for a cut. While seven of the nine strong committee voted to hold rates, if history does repeat itself, then it is possible more members will follow suit at the June meeting.

Meanwhile, UK equities continued to rise from the end of February, with the FTSE 100 hitting all-time highs this week, benefiting from strength in commodity and financial sectors.

Although the Federal Reserve (Fed) is unlikely to cut rates anytime soon given concerns around persistent price pressures facing the US economy, rate cutting cycles have already begun across Europe. Earlier this week, the Swedish Riksbank cut rates by 0.25% less than two months after the Swiss National Bank lowered their own rates by the same amount.

The European Central Bank (ECB) is widely expected to begin its rate cutting cycle in June. The BoE meanwhile indicated cuts could come in June, but Bailey emphasised that “June is not a fait accompli – each meeting is a new decision.”

Looking closer at the domestic picture, it looks as though rates will be cut faster than in the US but imported inflation due to currency weakness may give central banks pause for thought.

For imported inflation, look no further than Japan. The country’s glacial pace of policy tightening has seen its currency remain under pressure. Japanese authorities intervened last week as the yen aggressively sold off towards record lows of 160 yen to the dollar.2 This prompted Bank of Japan (BoJ) Governor Kazuo Ueda to warn markets that it may act if the yen continues to fall and could raise interest rates sooner.3

While the Fed is still trying to determine if it is even able to cut rates this year, persistent price pressures mean it is not in a rush. The UK and Eurozone have a more subdued growth outlook. Rate cuts would be welcome and should help increase economic momentum. However, the BoE and ECB are aware of the risks of weaker currencies leading to imported inflation. Meanwhile, Japan is facing the consequences of maintaining an ultra-loose policy that has sent the yen to the weakest level since the 1990s, which will likely prompt further increases in policy rates. These forces between the West and the East have left European central banks stuck in the middle.

[3] Bank of Japan, https://www.boj.or.jp/en/about/press/koen_2024/data/ko240508a1.pdf

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.